Video-assisted uniportal pulmonary segmentectomy: description of Safe Accurate Feasible and Easy technique and analysis of short-term outcome

Introduction

Uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (U-VATS) has become increasingly accepted as the newer alternative approach to conventional thoracoscopic surgery, for management of lung cancers across the globe (1). In our earlier publication we had shared our experience in the field of anatomical resection for carcinoma lung-(lobar resections and above), where U-VATS was found to be safe and oncologically sound (2). The Lung Cancer Study Group (LCSG) concluded that sub lobar resection was inferior to lobectomy due to higher local recurrences and higher deaths observed (3). There has been quite a few non randomised studies and meta-analysis after LCSG publication, which have shown sub lobar resections especially segmentectomy to be effective in select patients (4-8).

With the recent wide spread use of CT screening, increasing number of early stage lung cancer and preinvasive lesions are being picked up. Segmentectomy is more commonly being performed in patients having solitary pulmonary nodule ≤2 cm in an anatomical segment of lung, small T1N0M0 non-small cell lung cancer, ground glass opacity, benign nodules on imaging, nodule with very slow doubling time on serial imaging. The recent international multidisciplinary classification of adenocarcinoma of lung updated in 2011 reclassifies bronchio alveolar carcinoma (BAC) and introduced newer terminologies especially for patients who underwent resection, namely adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (MIA). These have been introduced based on the pathological, clinical data which show these two subsets have a very good survival rates post resection.

Given the advancement in imaging and pathological assessment, more and more of early stage tumours are being identified and sublobar resection offers an effective alternative, reducing the morbidity due to loss of lung volume. Minimal invasive thoracic surgery has become gold standard compared to conventional thoracotomy, when feasible. Of late interest has been in the performance of minimally invasive segmentectomy with uniportal technique. Recent publications have documented the feasibility and advantage of uniportal segmentectomy over multiport techniques (9,10). In this article we present our experience in U-VATS segmentectomy, which is currently the largest series in published literature at the time of submission. We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/vats-19-55).

Methods

Retrospective analysis of prospectively maintained database was done. Records of all patients who had undergone uniportal segmental resection from July 2014 to March 2018 were analysed. Preoperative patient’s parameters, intraoperative and postoperative outcomes were analysed. Statistical analysis was done using SPSS 17.0 software. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by institutional review board of Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital (K17-160). Individual Consent was waived off as this was a retrospective analysis and data was accessed after masking the patient’s identity.

Surgical technique

The most important prerequisite for segmentectomy is a clear knowledge of the segmental anatomy—of the segmental branches of arteries, veins and bronchus. The two sides of lung differ in their anatomy and so does individual segment. Some segments have only one vascular feeding branch, while some have more than one. Few have a recurrent branch of artery like the segment 1 on right side. In some segments, we need to dissect out the arterial branches distally to preserve the proximal branch and divide distally.

There are different techniques, used in the procedure of segmentectomy especially for defining the intersegmental plane like dissecting along the intersegmental vein and dividing them separately, use of Indo cyanine green (ICG) fluorescence to identify the segmental boundaries and of late 3D CT reconstruction aided performance of segmental resections (SAMURAI Technique) (11-13).

In our study, all patients were intubated using a double lumen endo tracheal tube. Patients were positioned in lateral position, with the involved side up, with a bridge under the chest to spread out the ribs. Operating surgeon stood on the ventral aspect of the patient, with assistant on the dorsal aspect. A single incision of length 4 cm was made in the anterior axillary line in 4th or 5th intercostals space depending on the location of the lesion. A few patients underwent subxiphoid incision for the surgery.

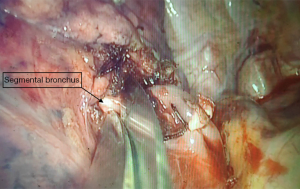

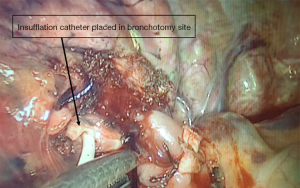

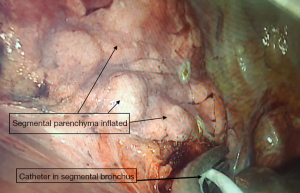

We describe Safe Accurate Feasible and Easy (SAFE) technique of segmentectomy by Jiang lei. In this approach after entering the thoracic cavity, the segment to be resected is identified and defined. Hilar dissection is carried out to identify the segmental artery, which is divided using endoscopic staplers. With further dissection, we approach the division of bronchus entering the segment. Once the bronchus to the segment to be resected is identified, ligature is passed around the proximal aspect of bronchus division and tightened. Using a sharp fine scissors, a small nick incision, about 5 mm in size, is given on the bronchus distal to the ligature. This opens up the airway leading to the segment of interest (Figure 1). A deep vein catheter is passed through the U-VATS incision and its tip placed into the opening created in the bronchus, tip directed distally (Figure 2). Air is pushed with help of a syringe till segmental parenchyma gets inflated. The segmental parenchyma gets insufflated exactly defining the segmental boundary (Figure 3) (Video 1). Once the boundary is defined, the catheter is removed and bronchus is divided with staplers and the distal bronchial stump is lifted up to dissect the parenchyma in its posterior aspect. This opens up a part of the intersegmental plane and helps us gain space for manoeuvring staplers for parenchymal resection, reducing the risk of damaging surrounding structures. Further dissection in the intersegmental plane is carried out using electro cautery and division is done using staplers. Separate identification of the intersegmental veins, which is tedious and time consuming, is not performed. We don’t perform the insufflations desufflation technique which has shortcomings like injury the lung (especially in emphysematous patients), time consuming as we need to wait for the lung to deflate. By selective canulation and insufflations, we overcome these issues as we are inflating only the segment that is going to be removed. We had employed this in all our segmental resections. After completion of procedure lung is insufflated to check for air leak and intercostal drain is placed.

Results

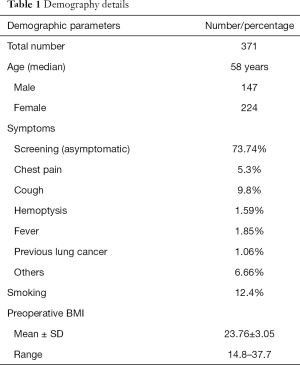

A total of 371 patients were identified from the prospectively maintained database. All these patients had undergone segmental resection of lung for various pathologies, over a period of 45 months (from July 2014 to March 2018). Median age was 58 years (range, 23–85 years). Female patients were more in number (male 147, female 224).

Most of these patients were asymptomatic, with radiological abnormality picked on screening CT scan of chest (73.74%). Other presentations include cough, haemoptysis, chest pain, which have been elaborated in Table 1. Smoking was less prevalent (12.4%). Table 1 describes the demographic details of patients included in the study.

Full table

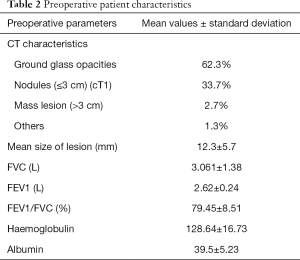

All these patients underwent a thorough work up. A HRCT was done to evaluate the lesion and the same was categorised based on morphology as ground glass opacity (GGO), ground glass nodules or mass lesions. The lesion size was documented as an average of the two perpendicular diameters. They were also assessed for the presence of any mediastinal nodes or other sites of disease. Patients, who had no other abnormalities, were further evaluated with pulmonary and cardiac functions to assess their fitness for surgery (Table 2).

Full table

All patients underwent U-VATS segmentectomy. Patients who had defined lesion localisable to an anatomical segment on CT scan underwent direct surgery. Those patients, in whom the lesions could not be localised to an anatomical segment, underwent pre-operative image guided wire localisation, for intraoperative identification.

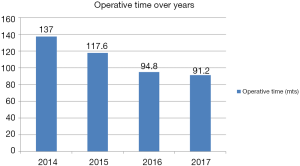

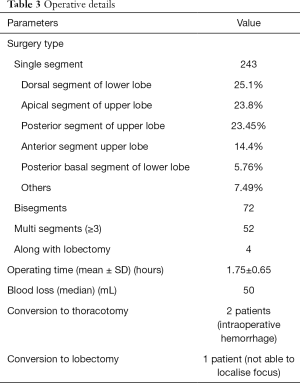

Surgical details are described in Table 3. Left sided surgeries were more common than right side. In 5 cases, bilateral segmental resections were done. Most of the resections were single segmental resections. The most common segment removed was dorsal segment of the lower lobe, followed by apical segment of upper lobe. (Table 3). Among the bisegmentectomy, apicoposterior segmentectomy was most common followed by lingulectomy. Among the multisegmental resection proximal segments of left upper lobe is most common, followed by basal segments of lower lobe. There were conversions to thoracotomy in two patients, both due to intraoperative bleeding, while in one case conversion to lobectomy was done due to inability to localise the lesion. Mean operating time was 105 minutes. Median blood loss was 50 mL. The operative time showed improvement over the years (Figure 4). There was no intra/peri-operative death.

Full table

On postoperative histopathological analysis, 29.4% patients had invasive tumour, 26.4% had AIS and 21.6% had MIA, 1.1% had both MIA and AIS component. 0.8% was metastatic lesion from other organ and 20.8% were benign lesions. Of the invasive tumours, most common was invasive adenocarcinoma (103 patients) followed by squamous cell carcinoma (3 patients), large cell carcinoma (2 patients) and small cell carcinoma (1 patient). Benign histology included Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (16 patients), hamartoma, bronchiectasis, Cysts, intra pulmonary fibrosis, tuberculosis.

In all patients a frozen analysis was done intraoperatively and in patients with invasive tumours, minimally invasive tumours and in AIS, a systematic nodal sampling was done. The median number of nodal stations sampled was 4. A median number of 9 nodes were removed. Nodes were positive in 4 patients (all N1 nodes), one node positive in two patients with AIS with lymphatic invasion, another in one invasive adenocarcinoma. Two nodes were positive in two patients, one with small cell carcinoma and other with invasive adenocarcinoma. All patients had a negative resection margin, with a minimum of 2 cm margins all around the tumour.

The mean postoperative stay was 3.7±1.8 days. The median duration of intercostal drainage was for 2.5 days. There were no in house/30-day mortality. Postoperative complications were minor in 6% (Clavien Dindo grade 1) with prolonged intercostal drainage being the most common. Few Grade 2 complications were seen in 3 cases, which included atrial fibrillation, pulmonary infection and wound discharge. All were managed conservatively with no patients requiring return to theatre.

Discussion

With the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) (14) indicating a reduction in the mortality rates in select patients with low dose CT scans, the use of CT screening has increased across the globe. Increasing use of screening CT scan in turn has resulted in increased frequency of detection of early lung cancers and radiological abnormalities, which were otherwise not routinely picked up on radiograph. The increased detection of these lesions has rekindled interest, in the use of sublobar resection for treatment of these suspicious lesions.

The publication of LCSG, may not be completely applicable to the present day scenario (3), with the greatly improved imaging techniques. While the study primarily used radiograph, current CT images not only helps detect earlier changes better, also the routine use of HRCT and PET CT scans have helped in the detection of nodal and distant metastasis. The International Association for Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) had redefined and classified the earlier used term of BAC into Minimal invasive adenocarcinoma [small solitary adenocarcinoma with either pure lepidic growth (AIS) or predominant lepidic growth with ≤5 mm invasion] and AIS variants. These have been proven to have comparatively better survival rates in comparison to invasive early lung cancer, close to 90–100% (15,16). Though the former is staged under stage IA1, while the latter is staged 0 (as per 8th edition of AJCC TNM staging), the studies described above have shown both to have near similar results.

Anatomical segmentectomy has many advantages over lobectomy as evident in the meta-analysis by Lim et al. (5). It can be safely performed in a patient with compromised lung function, helps in faster recovery and lesser complications compared to lobectomy and also helps in preserving the lung volume for future resection in case of recurrence or new primary in the lung. Anatomical segmentectomy is a demanding procedure and performance of the same by VATS is highly demanding. The Uniportal technique has a number of advantages over conventional multiport VATS—reducing the number of ports and thus reduction in the intercostals nerve damage, better and direct visualisation like that in a thoracotomy.

In this article we publish the largest experience on uniportal segmental resection (9,10,17-19). The other largest series include publications by Duan et al. (9) and Ali et al. (17). The latter had described their experience on subxiphoid approach.

The mean age was 56.24±1.15 in our study which was similar to the other studies (17-20) ranging from 53–56 years. The majority was females. Smoking was less prevalent in our study 12.4% similar to the other studies (12.55–23.7%) (9,17,18). Most of the patients were thin built as evident from the lower BMI. Ali et al. had also reported a lower BMI of 23.78 (17). Preoperative symptoms were reported in our study and majority were asymptomatic with lesions being detected on screening CT scan. This is in line with the increased detection rates of screening CT as found in the western countries (14), even though we had lower smoking rates.

The average operating time was 1.75±0.65 hours which was comparatively less in comparison to the others studies (range, 2.05–2.9 hours) (9,17-20). We had three conversions—two to thoracotomy due to intraoperative bleed and one to lobectomy due to non-identification of lesion. These were comparable to published literature (9,17,20). Our median nodal harvest was 9 which again is comparable to literature (17,19). On the post op histopathological analysis nearly half (48%) of our patients had preinvasive tumour (AIS and MIA). Since curative resections of these lesion are expected to give close to 100% 5-year survival, Uniportal VATS segmentectomy helps in appropriate management of these patients with parenchyma preservation and lesser morbidity. This is similar to studies published by Ali et al. and Duan et al. (9,17).

Conclusions

Increased detection of early stage lung cancers and precancerous lesions by CT screening and finding of enhanced survival in patients with AIS and MIA and the advantages of uniportal VATS guided segmentectomy and the literature suggesting sublobar resection having comparable survival rates among select patients with early stage tumours, U-VATS segmentectomy may be considered as a reasonable option in patients with limited stage early disease. Use of selective cannulation and open insufflations makes the procedure simpler and easier to perform. Longer follow up will help in confirming the oncological outcomes and help us in determining the difference in survival rates if any.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Kazuo Yoshida) for the series “Robotic VS Uniportal VATS” published in Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery. The article has undergone external peer review.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/vats-19-55

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/vats-19-55

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/vats-19-55). The series “Robotic VS Uniportal VATS” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by institutional review board of Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital (K17-160). Individual Consent was waived off as this was a retrospective analysis and data was accessed after masking the patient’s identity.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Bertolaccini L, Batirel H, Brunelli A, et al. Uniportal video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy: a consensus report from the Uniportal VATS Interest Group (UVIG) of the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2019;56:224-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Venkitaraman B, Lei J, Liang W, et al. Uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopy surgery in lung cancer: largest experience. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2019;27:559-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ginsberg RJ, Rubinstein LV. Randomized trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for T1 N0 non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer Study Group. Ann Thorac Surg 1995;60:615-22; discussion 622-623. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koike T, Yamato Y, Yoshiya K, et al. Intentional limited pulmonary resection for peripheral T1 N0 M0 small-sized lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003;125:924-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lim TY, Park S, Kang CH. A Meta-Analysis Comparing Lobectomy versus Segmentectomy in Stage I Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2019;52:195-204. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsutani Y, Miyata Y, Nakayama H, et al. Oncologic outcomes of segmentectomy compared with lobectomy for clinical stage IA lung adenocarcinoma: propensity score-matched analysis in a multicenter study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013;146:358-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yendamuri S, Sharma R, Demmy M, et al. Temporal trends in outcomes following sublobar and lobar resections for small (≤ 2 cm) non-small cell lung cancers--a Surveillance Epidemiology End Results database analysis. J Surg Res 2013;183:27-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang G, Wang Z, Sun X, et al. Uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic anatomic segmentectomy for small-sized lung cancer. J Vis Surg 2016;2:154. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Duan L, Jiang G, Yang Y. One hundred and fifty-six cases of anatomical pulmonary segmentectomy by uniportal video-assisted thoracic surgery: a 2-year learning experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2018;54:677-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee J, Lee JY, Choi JS, et al. Comparison of Uniportal versus Multiportal Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery Pulmonary Segmentectomy. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2019;52:141-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oizumi H, Kato H, Endoh M, et al. Techniques to define segmental anatomy during segmentectomy. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2014;3:170-5. [PubMed]

- Mun M, Okumura S, Nakao M, et al. Indocyanine green fluorescence-navigated thoracoscopic anatomical segmentectomy. J Vis Surg 2017;3:80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shimizu K, Nakazawa S, Nagashima T, et al. 3D-CT anatomy for VATS segmentectomy. J Vis Surg 2017;3:88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Low-Dose Computed Tomographic Screening. N Engl J Med 2011;365:395-409. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kadota K, Villena-Vargas J, Yoshizawa A, et al. Prognostic Significance of Adenocarcinoma in situ, Minimally Invasive Adenocarcinoma, and Nonmucinous Lepidic Predominant Invasive Adenocarcinoma of the Lung in Patients with Stage I Disease. Am J Surg Pathol 2014;38:448-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen T, Luo J, Gu H, et al. Should minimally invasive lung adenocarcinoma be transferred from stage IA1 to stage 0 in future updates of the TNM staging system? J Thorac Dis 2018;10:6247-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ali J, Haiyang F, Aresu G, et al. Uniportal Subxiphoid Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Anatomical Segmentectomy: Technique and Results. Ann Thorac Surg 2018;106:1519-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aresu G, Weaver H, Wu L, et al. The Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital uniportal subxiphoid approach for lung segmentectomies. J Vis Surg 2016;2:172. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheng K, Zheng B, Zhang S, et al. Feasibility and learning curve of uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic segmentectomy. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:S229-34. [PubMed]

- Han KN, Kim HK, Choi YH. Comparison of single port versus multiport thoracoscopic segmentectomy. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:S279-86. [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Venkitaraman B, Cai J, Ma X, Chen Z, Shi Z, Jiang L. Video-assisted uniportal pulmonary segmentectomy: description of Safe Accurate Feasible and Easy technique and analysis of short-term outcome. Video-assist Thorac Surg 2020;5:21.