Certification in VATS surgery

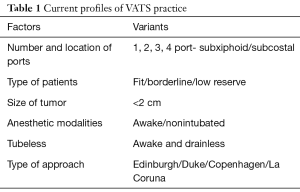

Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) has been introduced into clinical practice as of the early 1990’s but, to the purpose of certification, credentialing or privilege seeking, may still be considered a new technique (1). In fact, the evolution of the VATS technique into a VATS philosophy, with the multiple interpretations of the thoracoscopic approach to the chest as well the modifications of the anesthetic management, has made VATS an ever changing approach with many surgeons experiencing difficulties at staying abreast of all possible innovations in order to translate them into clinical practice (Table 1). Certification in thoracic surgery becomes of significant relevance especially when the number of certified thoracic surgeons practicing in the thoracic surgical unit has been proved to be one of the factors, along with volume of procedures, that may play a crucial role in determining improved mortality rates after pulmonary resection (2).

Full table

This paper deals with the pathways of certification, credentialing or privilege seeking—outside the standard environment of the residency programs—that a surgeon can select in order to proficiently practice VATS with special consideration to VATS lobectomy.

The process of certification

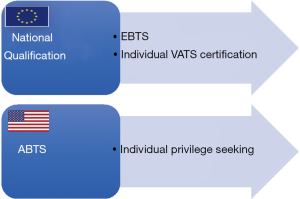

In order for a surgeon to be able to practice a new technique resulting from the introduction of new technology (like VATS), he or she needs to be certified in the specific specialty and acquire credentialing and/or seek privileges to perform that particular procedure at a local institutional level (3). The latter combination of processes is predominantly relevant in the United States whereas, in Europe, the issue of credentialing/privilege seeking is virtually nonexistent and the national specialty training programs are the sole responsible for certification (3). In this setting, in order for a thoracic unit to be qualified in Europe, at least the Chief Thoracic Surgeon should be certified by the European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS)-European Board of Thoracic Surgery (EBTS) (3). Nevertheless, the EBTS certification does not focus on the possession of VATS skill set.

Blackmon and colleagues have identified two distinct pathways for credentialing in thoracic surgical procedures in the United States (1). The first, relates to the possibility of expanding the thoracic surgeon’s skill set with existing procedures to which he/she had not been exposed to during training (1). Not surprisingly, given the still existing variability of practice worldwide, VATS is among these procedures (1,4). The second scenario relates to the procedures which are not considered germane to the American Board of Thoracic Surgery (ABTS) defined skill set but in which thoracic surgeons may play a “clinical leadership role”—stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) is a fulgid example of such procedures (1).

At a national or international level, a series of intertwining factors needs to be considered when the process of the certification is structured (Figure 1). These are relevant to the candidate, the tutor, the certifying institution and the certifying body. In addition, the current status of refinement of the available technology sets the timing for a change in the certification strategies and its complexity. In this setting, certification in VATS surgery is a clear example. The existence of different VATS approaches has made learning VATS a multifaceted undertaking depending on the institution where the training curriculum is taking place. In fact, the likelihood of being exposed to all aspects of VATS at the same time in one center can be limited and, therefore, the volume of cases per single procedure may not be sufficient for the trainee to complete the curriculum. Reportedly, some of the highest volume VATS surgeons in the world tend to accumulate experience with one procedure (5); when a different operative strategy is adopted, they tend to gradually shift their entire volume on the new procedure in order to rapidly develop a significant expertise.

Blackmon and coworkers have emphasized four tenets that are crucial to structuring a successful privileging process which can be adapted to suit the certification in VATS, namely: (I) clear lines of responsibility for the certification/privileging process; (II) supportive governance structures; (III) accepted standards for certification/privileging; and (IV) a culture of continuous improvement and evaluation of certification/privileging process outcomes (1).

The candidate

The controversy still exists as to whether adequate certification in VATS surgery requires a substantial curriculum demonstrating sufficient exposure to the basics of open thoracic surgery (4,6). Recently, the suggestion that proficient VATS surgeons can be trained irrespective of their open experience appeared in a best evidence paper (7). However, experience with conventional three-port VATS is found to be necessary when the development of an uniportal expertise is considered (8). Beyond their original surgical residency programs, subsequent fellowships in minimally invasive thoracic surgery and ad hoc VATS courses, young trainees usually come across several other opportunities to be exposed to VATS, including animal or cadaver labs and simulation theatres (9-11). On the other hand, established (i.e., more than 10 years in independent practice) consultants derive their VATS skill set from observing a proficient VATS surgeon, reading the technical lecture, rarely being mentored by a surgeon in the same staff, and, most importantly, by trial and error (9,12). In a survey on VATS exposure conducted among residents, CT residency and mentoring received from same staff surgeons were the VATS training modalities perceived as most useful to learn the technique (9). In this context, the assessment of proficiency in VATS can be defined through established protocols and theoretical tests which can support the certification process (13). Senior consultants approaching VATS major pulmonary resections could also benefit in the learning curve from a standardized self assessment of performance based on well recognized skill improvement criteria (12).

Institutional credentialing and privilege seeking

In the context of a focused professional practice evaluation, five levels of competence are functional to the credentialing/privilege seeking process (1). This pathway is developed on a series of learning steps characterized by an increasing level of supervision, from the attendance to a specific course without learning verification to the supervised performance of clinical procedures (1). One definitive advantage of such classification lies into the possibility of agreeing on a common terminology and steps on the sequence of the multilevel learning curve necessary to be granted privileges (1).

This author believes that another potential advantage of implementing this supervised learning pathway consists in the ability for several institutions to contribute to this process with their best educational offer. In other words, in a structured educational network centered on major academic centers, district and community hospitals could provide levels 1 to 3 while government-ruled institutions dedicated to patient care could contribute to the educational pathway by covering level 4 of the supervised learning curve. Accordingly, exposure to VATS training with the attendant certification would be based on significant volumes and multileveled quality thanks to the participation of different institutions and hospitals in the same training district. This distribution of training activities would in turn demonstrate the absolute value of educational networking involving all types of health care providers. Moreover, in Europe, irrespective of the institutional affiliation, each unit should comply with the criteria for structuring and qualification of thoracic surgery already published in 2014 (3). The observance of these criteria is somehow propedeutic for thoracic surgical units to deliver homogenous surgical treatment characterized by comparable outcomes.

The certifying body

There is no doubt that certifying bodies around the world are focusing on ensuring continuous professional development according to stringent quality criteria. In this context, the implementation of national and/or international surgical databases allows for the definition of risk scores aiming at performance stratification (14,15). In addition, the stipulation of intersocietal agreements on common training curricula will clarify standing issues and dissipate the existing gray zones by defining who does what, when and for which indications (16,17). Accordingly, certification in VATS will be soon become an agreed, structured, internationally recognized process integrated in a multidisciplinary training/credentialing pathway aimed at assessing competency as a specific individual trait (18). In this setting, the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons has been functional to create the foundations of a comprehensive educational platform dedicated to thoracic surgeons worldwide (19). Currently, this platform already includes several VATS courses, the completion of which can be recognized to the purpose of obtaining EBTS certification or as stand alone ESTS sponsored certificate of proficiency in VATS.

Conclusions

Interesting perspectives are lining up at the horizon of the process of certification in VATS surgery, all aiming at defining a shared multileveled curriculum worldwide (1). In this setting, essential components of VATS training are being revised with the increasing availability of advanced simulators (20). In addition, more objectives methods for determining proficiency in VATS and a greater attention to non technical factors crucial to efficiency of the VATS practice have been developed in order to make this minimally invasive thoracic surgery technique more standardized, teachable and diffused for the supreme benefit of our patients (21,22).

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Marco Scarci and Roberto Crisci) for the series “VATS Special Issue dedicated to the 4th international VATS Symposium 2017” published in Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery. The article did not undergo external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: The author has completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/vats.2017.08.13). The series “VATS Special Issue dedicated to the 4th international VATS Symposium 2017” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. GR serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery from Jun 2016 to May 2019. The author has no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The author is accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Abdelsattar ZM, Allen MS, Shen KR, et al. Variation in Hospital Adoption Rates of Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Lobectomy for Lung Cancer and the Effect on Outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg 2017;103:454-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nagayasu T, Sato S, Yamamoto H, et al. The impact of certification of general thoracic surgeons on lung cancer mortality: a survey by The Japanese Association for Thoracic Surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;49:e134-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brunelli A, Falcoz PE, D'Amico T, et al. European guidelines on structure and qualification of general thoracic surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014;45:779-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rocco G, Internullo E, Cassivi SD, et al. The variability of practice in minimally invasive thoracic surgery for pulmonary resections. Thorac Surg Clin 2008;18:235-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sihoe ADL, Han B, Yang TY, et al. The Advent of Ultra-high Volume Thoracic Surgical Centers in Shanghai. World J Surg 2017; [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Billè A, Okiror L, Harrison-Phipps K, et al. Does Previous Surgical Training Impact the Learning Curve in Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery Lobectomy for Trainees? Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016;64:343-7. [PubMed]

- Okyere S, Attia R, Toufektzian L, et al. Is the learning curve for video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy affected by prior experience in open lobectomy? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2015;21:108-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martin-Ucar AE, Aragon J, Bolufer Nadal S, et al. The influence of prior multiport experience on the learning curve for single-port thoracoscopic lobectomy: a multicentre comparative study†. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2017;51:1183-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boffa DJ, Gangadharan S, Kent M, et al. Self-perceived video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy proficiency by recent graduates of North American thoracic residencies. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2012;14:797-800. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jensen K, Bjerrum F, Hansen HJ, et al. Using virtual reality simulation to assess competence in video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) lobectomy. Surg Endosc 2017;31:2520-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jensen K, Bjerrum F, Hansen HJ, et al. A new possibility in thoracoscopic virtual reality simulation training: development and testing of a novel virtual reality simulator for video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery lobectomy. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2015;21:420-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rocco G. The impact of outliers on the mean in the evolution of video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2017;51:613-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Konge L, Lehnert P, Hansen HJ, et al. Reliable and valid assessment of performance in thoracoscopy. Surg Endosc 2012;26:1624-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brunelli A, Rocco G, Van Raemdonck D, et al. Lessons learned from the European thoracic surgery database: the Composite Performance Score. Eur J Surg Oncol 2010;36:S93-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brunelli A. European Society of Thoracic Surgeons Risk Scores. Thorac Surg Clin 2017;27:297-302. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mullon JJ, Burkart KM, Silvestri G, et al. Interventional Pulmonology Fellowship Accreditation Standards: Executive Summary of the Multisociety Interventional Pulmonology Fellowship Accreditation Committee. Chest 2017;151:1114-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gamarra F, Noël JL, Brunelli A, et al. Thoracic oncology HERMES: European curriculum recommendations for training in thoracic oncology. Breathe (Sheff) 2016;12:249-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Potts JR 3rd. Assessment of Competence: The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education/Residency Review Committee Perspective. Surg Clin North Am 2016;96:15-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Massard G, Rocco G, Venuta F. The European educational platform on thoracic surgery. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S276-83. [PubMed]

- Jensen K, Ringsted C, Hansen HJ, et al. Simulation-based training for thoracoscopic lobectomy: a randomized controlled trial: virtual-reality versus black-box simulation. Surg Endosc 2014;28:1821-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Savran MM, Hansen HJ, Petersen RH, et al. Development and validation of a theoretical test of proficiency for video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) lobectomy. Surg Endosc 2015;29:2598-604. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gjeraa K, Mundt AS, Spanager L, et al. Important Non-Technical Skills in Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery Lobectomy: Team Perspectives. Ann Thorac Surg 2017;104:329-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Rocco G. Certification in VATS surgery. Video-assist Thorac Surg 2017;2:50.