Videothoracoscopic thymectomy for myasthenia gravis: an overview of complications on 387 VATS thymectomies for myasthenia gravis

Introduction

Video assisted thoracoscopic (VAT) thymectomy operations for the treatment of myasthenia gravis (MG) and thymic malignancies are increasingly preferred (1,2).

Operative and postoperative morbidity, mortality and complete stable remission rates of VAT thymectomy procedures have been shown to be similar to open procedures, even the duration of hospital stay, perioperative blood loss and patient satisfaction parameters have been demonstrated to be superior in VAT thymectomy procedures (1,2). However, these procedures have the potential to cause dangerous intraoperative/postoperative complications. Management strategies should be known to prevent morbidity and mortality (3). In this article, we aimed to evaluate the intraoperative events and early postoperative complications of VAT thymectomy operations in myasthenic patients, in one of the largest single centre experience.

Patients and methods

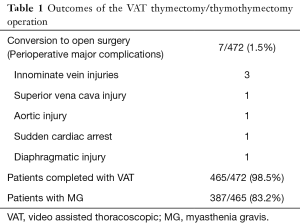

Four hundred and seventy-two VAT thymectomy operations performed in Department of Thoracic Surgery, at Istanbul University, Istanbul Medical School, between June 2002 and November 2016. Seven patients (1.4%) were converted to open due to various reasons which will be described later in this article, 465 were completed by VAT and from them 387 had myasthenia gravis (MG). Seventy-eight patients were operated on for thymoma, for parathyroid adenoma, for suspected thymic malignancy, for thymic carcinoids and thymic cysts. Patients with MG included in this study in order to evaluate also disease combined complications. The data was recorded prospectively and evaluated retrospectively. In addition to operative and post-operative complications; age, sex, duration of disease, body mass index, prescribed medication, duration of the operation, chest tube duration, length of postoperative hospital stay, and pain score using a visual analogue scale were analysed.

Patients with generalised MG were recommended for thymectomy by the department of neurology. We performed right sided three portal VAT thymectomy which has been defined previously (4).

Results

Of the 472 procedures (403 non thymoma and 69 thymoma patients), 7 patients (1.4%) experienced major perioperative complications and converted to open surgery. After the subtraction of 78 non myasthenic patients, we had a group of 387 patients with MG, VAT thymectomy population included this study (Table 1).

Full table

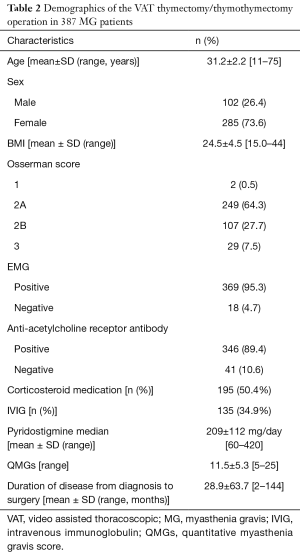

The mean age was 31.2 years (range, 11–75 years); 285 (73.6%) of the patients were female, and 102 (26.4%) were male. The mean body mass index (BMI) of the patients was 24.6±4.5. Of all of the patients, 2 (0.5%) were Osserman 1, 249 (64.3%) were Osserman 2A, 107 (27.7%) were Osserman 2B and 29 (7.5%) were Osserman 3. Electromyography was positive in 284 (73.5%) patients, acetylcholine receptor antibody test was positive in 244 (63%) patients and the mean QMG was calculated to be 9.7. Three hundred fifty (90.4%) patients were treated with pyridostigmine bromide, with an average dosage of 209±112 mg/day. One hundred ninety five (50.4%) patients also received corticosteroid medication and 135 (34.9%) patients received intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) treatment prior to the surgery. The average time between the diagnosis and thymectomy was 28.9±63.7 months (Table 2).

Full table

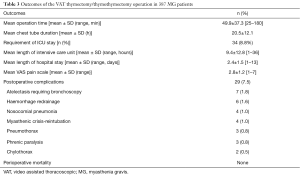

The average duration of the operation was 49.9±37.3 min (range, 25–180 min). Thirty three (8.8%) patients required a mean of 9.4±12.8 h of mechanical ventilation postoperatively. Twenty-nine (7.5%) patients developed complications. The average duration of drainage was 36.6±24.8 h. The average pain score using a visual analogue scale was 2.8±1.2 (range, 1–7). The average time of discharge was 2.4±1.5 days (range, 1–13 days). The long term histopathological examination was reported as thymoma in 54 (14%) patients in MG group (Table 3).

Full table

Discussion

VAT thymectomy has been shown to provide better or at least similar long-term outcomes and quality of life compared to open surgery (5). Open surgery and thoracoscopic procedures have been shown to be associated with equivalent long-term symptomatic improvement, in the same study thoracoscopic approach was associated with significantly less blood loss, shorter hospital stay and decreased requirement for postoperative narcotic analgesia (6).

A recent study reported that the thoracoscopic thymectomy is a safe and minimally morbid operation that is successful in improving MG symptoms. VAT thymectomy resulted in a decrease in the amount of medication, length of hospital stay and admission-related hospital expenses, and a reduced or similar operative time compared with that reported for a historical series of open thymectomies (7).

We previously demonstrated that a certain group of VAT thymectomy patients (33.7%) could be discharged the next morning following surgery (8). For this reason, VAT thymectomy could also be considered as a model of fast-track surgery, with early discharge period and short duration of drainage time. However, this operation requires a steep learning curve for surgeons and it is one of the most dangerous operations in unexperienced surgeons’ hands. Even experienced surgeons in thymic procedures may face catastrophic complications including; cardiac arrest, aortic and superior vena caval ruptures. VAT thymectomy patients may also develop postoperative complications similar to the other VAT surgery patients such as; there are 7 patients with atelectasis requiring bronchoscopy (1.8%), 6 patients with undrained haemothorax requiring redrainage (1.6%), 4 patients with nosocomial pneumonia (1.0%). One of the best result in our study is only 4 patients developed myasthenic crisis requiring reintubation (1.0%), 3 phrenic paralysis (0.8%)

Another possible problem for many surgeons with a right-sided approach is the possible inadequacy of visualisation of the left phrenic nerve. During a thymectomy, the left phrenic nerve should be seen and dissected meticulously to prevent an injury to the nerve. Especially in patients with high BMI over 35, left phrenic nerve cannot be evaluated safely and may be injured. Surgeons may consider to approach bilaterally in such patients.

VAT thymectomy for treatment of myasthenia gravis is a relative safe procedure but potential dangerous operative and postoperative complications and management strategies should kept in mind to prevent morbidity and mortality.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery for the series “Minimally invasive VATS thymectomy for Myasthenia Gravis”. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/vats.2017.03.07). The series “Minimally invasive VATS thymectomy for Myasthenia Gravis” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. AP served as the unpaid Guest Editor of the series and serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery from Aug 2016 to May 2019. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Zahid I, Sharif S, Routledge T, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery or transsternal thymectomy in the treatment of myasthenia gravis? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2011;12:40-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Odaka M, Shibasaki T, Asano H, et al. Feasibility of thoracoscopic thymectomy for treatment of early-stage thymoma. Asian J Endosc Surg 2015;8:439-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Özkan B, Toker A. Catastrophes during video-assisted thoracoscopic thymus surgery for myasthenia gravis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2016;23:450-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Toker A, Tanju S, Ziyade S, et al. Learning curve in videothoracoscopic thymectomy: how many operations and in which situations? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008;34:155-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bachmann K, Burkhardt D, Schreiter I, et al. Long-term outcome and quality of life after open and thoracoscopic thymectomy for myasthenia gravis: analysis of 131 patients. Surg Endosc 2008;22:2470-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wagner AJ, Cortes RA, Strober J, et al. Long-term follow-up after thymectomy for myasthenia gravis: thoracoscopic vs open. J Pediatr Surg 2006;41:50-4; discussion 50-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Christison-Lagay E, Dharia B, Vajsar J, et al. Efficacy and safety of thoracoscopic thymectomy in the treatment of juvenile myasthenia gravis. Pediatr Surg Int 2013;29:583-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Toker A, Tanju S, Ziyade S, et al. Early outcomes of video-assisted thoracoscopic resection of thymus in 181 patients with myasthenia gravis: who are the candidates for the next morning discharge? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2009;9:995-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Toker A, Özkan B. Videothoracoscopic thymectomy for myasthenia gravis: an overview of complications on 387 VATS thymectomies for myasthenia gravis. Video-assist Thorac Surg 2017;2:19.